|

| 4% of the South African flag |

This is a question that each and every single person should ask themselves.

Putting your head in the sand and hoping that your compulsory monthly contributions to your company's pension fund (if you are lucky enough to have one) is going to be enough for your retirement (early or otherwise) is not a very good strategy.

The problem is that no one really ever gives us a proper number to aim for. Maybe you have seen the frequently quoted rule of thumb which the industry seems to love - you need a lumpsum that will allow you to draw 75% of your final salary. Nice and fuzzy. Not very helpful...

What will your final salary be?

What lumpsum will give you 75% of that?

Will that be enough for your monthly expenses?

And then my main problem with this estimate (and many of the others I have seen) is that it is based on income. And this is very dangerous because the amount of money you need in retirement has absolutely zero to do with how much you earn and everything to do with how much you spend.

And so for that reason, I prefer the 4% Rule (or Rule of 300) because it depends on the only thing that matters – your expenses in retirement.

Just a quick recap then - the 4% Rule comes from a study done in the United States, which looked at data spanning from 1925 to 1995. The study wanted to determine the highest percentage that someone could withdraw from a portfolio made up of bonds and shares in their first year of retirement, and then adjust that amount for inflation each year for a period of 30 years, such that they would never run out of money. This starting percentage was found to be 4% - and hence the 4% rule.

But people generally don’t like working with percentages and annual expenses so, if you just rearrange the Maths a little, you find that in order to be financially free/ retire securely you need an investment amount equal to your monthly expenses multiplied by 300 (hence the rule is also known as the Rule of 300).

I did a more detailed explanation in this post. In the two years since that post, I have done a lot of reading around the rule and it’s shortcomings, and it seems that some people are less than convinced.

Some of the contentious points are:

- The study was done in America and is therefore only applicable to Americans.

- It only covers 30 years – most retirements will be longer than that since people are living longer and longer.

And then I can add some additional criticisms from us folk here at the bottom end of Africa:

- The Rand is going to shit.

- We have had some, let’s call them um… below-average, politicians in positions of power

I did this in two ways:

- Don’t reinvent the wheel – there is an existing study which looked at how the 4% Rule would have worked out in numerous countries across the world. Luckily for us, South Africa was included in the study, and so we can just check the results. The study used data from 1900 up until 2008

- Reinvent the wheel anyway – the above study made certain assumptions about portfolio allocations, and didn’t address retirement duration (something that I am interested in since I plan on retiring a lot earlier than what is considered “normal”). And so I decided to run my own little investigation. The data I used was from 1925 up until 2014.

Just an upfront warning - this post is on the longer side, so best you get your beverage fo choice before proceeding...

Right onto the juicy part!

An International Perspective on Safe Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Savings

After my initial post on the 4% Rule, one of the blog's readers emailed me a paper written by a Professor Wade Pfau (in truth you can leave the professor part out, because anyone whose surname starts with Pf just sounds really smart - or is that just me?)

Professor Pfau decided to extend the 4% Rule study to cover more years and more countries to see how it played out. He crunched some serious numbers using 109 years of data across 17 countries, and put his findings together into a paper titled “An International Perspective on Safe Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Savings: The Demise of the 4 Percent Rule?”

If you want, you can download the paper here, but I think the findings are nicely summarised as:

“From an international perspective, a 4 percent real withdrawal rate is surprisingly risky. Even with some overly optimistic assumptions, it would have only provided "safety" in 4 of the 17 countries. A fixed asset allocation split evenly between stocks and bonds would have failed at some point in all 17 countries.”

Also worth mentioning, is that for a lot of his analysis he considered a portfolio allocation that had the optimal split between equities and bonds – something which can only be done in hindsight and impossible to achieve in reality. He calls it the “perfect foresight” assumption.

So from his findings, not all peaches and cream.

I also just want to pull out some of the 1000 words from his paper – I found these two particularly interesting...

The first picture shows the results of the highest starting withdrawal rate that would guarantee never running out of money over a 30 year period (the cool kids call this SAFEMAX) for each of the 17 countries he looked at. (Based on the highlighting, no prizes for guessing where Professor Pfau is from :))

So the only countries in which the 4% rule worked for all periods were Canada, Sweden, Denmark and the USA. And because of the “perfect foresight” assumption, this an absolute best case scenario. And boy were you screwed if you tried this in Japan!

I was also really surprised by some of the European countries, but the SAFEMAX dates in the table scream two events at me – WWI and WWII. Understandable!

South Africa was a little behind, but not too far off at 3.84%. (Out of interest a 3.84% SAFEMAX turns the Rule of 300 into a Rule of 312.5 - i.e. you would need 312.5 times your expenses.)

This next picture was really interesting. It shows the SAFEMAX for each country based on the % allocation to equities. Apologies, the picture quality is not that great...

What becomes apparent is that for most countries you need more than 50% in equities if you want the highest SAFEMAX – only Switzerland had it’s highest SAFEMAX with an equity allocation less than 48%. In other words, you need growth assets, and quite a few of them, if you want to give your retirement portfolio a fair shot!

South Africa can also count itself as one of only 3 countries where a 100% equity allocation resulted in the highest SAFEMAX. But that might have to do with the fact that we had the best performing equity market over the last 100 years.

My Own Analysis

While I found Professor Pfau’s paper great, I also wanted to conduct my own investigation into the 4% rule in South Africa - mainly for these two reasons (but also because I thought it would be both challenging and fun!)- I wanted to check out how different fixed asset allocations would behave (something that would be far more practical and implementable than the perfect foresight assumption).

- I wanted to check how things would play out over longer time periods – 40 and 50 years. I was especially interested in this because if I reach my financial freedom target, I would want some comfort in knowing that my money would last me until the end…

First Disclaimer:

This entire investigation and analysis was done using some historical Bond and Stock data which I managed to find here. This is the best data that l could get for free (my apologies for being cheap :)). However, since it is from an asset manager, I am fairly confident it is accurate and reliable – but yeah you never know…

Second Disclaimer:

I then had to transpose the data into an excel spreadsheet to run the calculations and simulations. It was a very manual and tedious process. To the best of my knowledge, the data was transposed correctly, but there was copious amounts of coffee involved, and as my wife will be quick to point out, I do make mistakes! So I am not making any guarantees, and of course the outcome is only as good as the input.

So with that out the way, lets do this!

The 4% Rule In South Africa - Historical Data

Historical Returns Of Asset Classes In South Africa

The data I found is great because it contains “real returns”

and seems to include dividends. So that means it removes the complication of

inflation and dividend reinvestment.

I averaged out everything, and found the real returns to be:

Bonds – 2%

Equities – 10.2%

(These numbers fall more or less in line with what I found using other data. In fact the above numbers are a little better)

I then needed one more asset class for the analysis - cash. I assumed this to

give a 0% real return. I.e. cash just keeps up inflation (in truth you may be able to do a little better than this).

(Note that I didn’t consider Listed Property separately

(maybe I should have?) because this is inherently covered by equities – the

index includes listed property companies.)

Asset Allocations

I have been mulling over what a good asset allocation for retirement would be for a while now. I have settled on a number of different options, only to come up with something “better” every few months. To be honest, I am still not decided (which is fine, still plenty of time to go…)Some of the options I have considered, and the ones I will use for the analysis are:

- 100% Equities (Based on Prof Pfau’s results for South Africa)

- 50% Equities, 50% Bonds (The original 4% Rule allocation)

- 90% Equities, 10% Cash (This is my current preferred one – the 10% cash allows a buffer and emergency stash should the markets pull a nasty)

- 75% Equities, 25% Bonds (A sort of Reg 28 compliant mix)

- 75% Equities, 15% Bonds, 10% Cash (A different flavour of Reg 28)

- 60% Equities, 30% Bonds, 10% Cash (This just seemed like a “good mix”)

I must also mention that the way I ran the calculations is that after each year the portfolio would be re-balanced to the targeted allocation.You may think that not being allowed to re-balance and change over the course of retirement is unrealistic and could even be detrimental, but I think something like this may actually be to a retiree’s advantage - because we all know how well people do with options once emotions get involved….

The Calculations

The retirement scenarios were run as follows:- First I considered someone who retired at the start of the first year of available data – i.e. 1925.

- The retiree’s portfolio was allocated to each of the above mentioned asset allocations.

- The retiree then withdraws 3.0% of the portfolio at the start of the year, the years return (weighted according to asset allocation) is added to the portfolio at the end of the year, and then the asset classes are re-balanced.

- This was repeated for each subsequent year of their “retirement”. (Don’t have to adjust the withdrawals for inflation, since returns are already inflation adjusted).

- At the end of 30, 40 and 50 years, the portfolio value was checked to see if it had ever gone negative – i.e. the retiree ran out of money. I would mark this as an “unsuccessful retirement”.

- I repeated this for starting withdrawal rates of 3.0% to 6.0% (in 0.1% increments).

- Repeat the calculations for someone who retired in 1926, 1927 etc. etc.

- Count the number of successful retirements and express it as a percentage for each starting withdrawal rate and each asset allocation over 30, 40 and 50 years.

The Results

Okay who cares about all that! Show me the good stuff!Would the 4% Rule have worked In South Africa?

Drum roll please.....

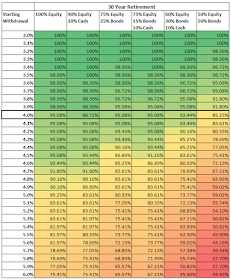

The tables below show the chances of success for various starting withdrawals for each asset allocation for 30, 40 and 50 year retirements (where a successful retirement is defined as “not running out of money over the period”)

30 Year Retirement

- A 100% success rate was possible up to 3.5% using an allocation of 90% equity and 10% cash.

- The original 4% rule didn’t give a 100% success rate for any of the asset allocations. Success rates above 95% were possible when the allocation to equities was high. The original 4% rule, which says 50% equity and 50% bonds had a success rate of only 85% - not the sure bet we were hoping for?

- Higher starting withdrawals become dangerous, and more so with a low equity component. A 6% starting withdrawal with only 50% in equities had a 1 in 3 chance of succeeding.

40 Year Retirement

- I only show starting withdrawals rates up to 4.5% because things go downhill pretty quickly over this longer time period

- 100% success rates were possible for starting withdrawals up to 3.2%

- The 4% rule gave 94% success rates when the asset allocation contained a high percentage of equities.

- We again see that higher equity allocations resulted in higher success rates.

50 Year Retirement

- While there was a noticeable degradation in performance when moving from a 30 year retirement to a 40 year retirement, the effect of moving from a 40 year retirement to a 50 year retirement is less pronounced.

- Starting withdrawals higher than 4.5% are not shown because the success rates become very low

- 100% success rates were possible at a 3.1% starting withdrawal for high equity portfolios.

- The 4% rule gave success rates in excess of 90% when the equity component was high.

- The trend of lower equity resulting in lower success rates is apparent.

Conclusions From Historical Data

- Historically the 4% Rule would have worked fairly well in South Africa, especially over a 30 year period where success rates of over 95% were possible.

- The longer the retirement period, the greater the chances of a retiree’s money running out.

- The best chance of success would have been achieved by a high allocation to equities.

- 100 % success rates would have been possible for the following starting withdrawals over the following periods. (The asset allocation which was used to achieve the highest starting withdrawal is also shown).

Retirement

Period

|

Highest

Initial Drawdown For 100% Success

|

Asset

Allocation At Highest Successful Drawdown

|

30 Years

|

3.5%

|

90% Equities, 10% Cash

|

40 Years

|

3.2%

|

100% Equities OR

90% Equities, 10% Cash

|

50 Years

|

3.1%

|

100% Equities OR

90% Equities, 10% Cash

|

The 4% Rule In South Africa - Monte Carlo Simulations

Using historical data to investigate how the 4% rule would have played out is certainly useful, but it has some limitations.

- The middle years are over-represented while the starting and ending years are under-represented . The years in the middle of the data appear in almost all the 50 year periods for example while the 1929 data point appears in only one.

- There is only one way each period could play out – and that is in sequential order. But what if the World War II returns were immediately followed by a 2008 style financial crisis?

- The data is limited – we can only run a certain number of simulations based on the data that is available.

Luckily there is a way around this – it’s called Monte Carlo simulations and it works as follows:

- Pick a random return from the data set and use that for the current scenario’s first year return.

- For the following year, again pick a random return (i.e. not the next sequential return from the data set) and use that as the return.

- Repeat this for each year of the retirement

- Run this as many times as you like – usually in the thousands.

The Results

Okay theory out the way, onto the results!The tables below are the same as for the historical data - they show the success rates for various starting withdrawals for each asset allocation over 30, 40 and 50 year retirements (where a successful retirement is defined as “not running out of money over the period”)

30 Year Retirement

- Interesting to note – there was no SAFEMAX. All asset allocations had failures over the 30 year period.

- At a 4% starting withdrawal, the high equity portfolio’s achieved a success rates above 95% - which is pretty much in line with the analysis done using the historical data.

- The trend of higher equity allocations resulting in higher success rates is less pronounced.

40 Year Retirement

- The 4% rule gives success rates in the 90’s for high equity allocations

- The success rate degradation when moving from a 30 to 40 year retirement is less pronounced. The 40 year retirement scenario’s are on average 4.1% less successful than the 30 year scenario’s

50 Year Retirement

- Over 50 years, the success rate of the 4% rule falls below 90% for all portfolio’s.

- At higher starting withdrawals, success rates are improved with higher equity allocations.

Conclusions From Monte Carlo Simulations

- Using Monte Carlo simulations, even with starting withdrawals as low as 3%, it was not possible to achieve a 100% success rate. The catch-all characteristic of the simulations just goes to show that there can (and probably) will be scenario’s where the 4% (or even the 3%) rule will not work – nothing is certain (it never is)

- The longer the retirement period, the greater the chances of a retiree’s money running out.

- The best chance of success would have been achieved by a high allocation to equities, although it is less pronounced in the Monte Carlo simulations compared to the historical data simulations.

The Good, The Bad And The Ugly

And after all that reading, I am going to tell you that all of this is moot anyways - because it is unlikely that you will have 100% of your investment in South Africa.

Investing 101 says that you will have some diversification offshore, and even if you didn’t you would naturally get some anyways – the majority of South African listed company's revenues come from overseas.

My pleasure for wasting your time :)

But having said that, I still think the results are useful, and so here are some concluding thoughts…

The Good

Even though the original 4% Rule didn’t give a 100% success rate for any asset allocation or time period, it is still and excellent tangible rule of thumb:- In most scenario’s you end up with way more money than what you would have started with. This is a fantastic problem to have!

- If you found yourself on one of the few "unlucky” paths, and your portfolio was to experience a significant loss, which could result in you running out of money, you wouldn’t merrily continue holidaying and spending as if you had no worries. No, you would likely cut some of your spending to compensate.

- You could be clever with asset allocation, and if you had some cash and or bonds, you could drawdown from only those assets if equities were to experience a bad crash. A 10% cash allocation could last you around 3 years if you wanted to wait for markets to recover

- Research shows that as people age, they spend less. So as you get further and further down retirement avenue, you will find that the shops which line the street sell goods which are cheaper and cheaper…

The Bad

There are still some factors which can unhinge a 4% spending plan- The 4% rule is based on official CPI inflation. Your retirement inflation could be above the official CPI inflation rate (medical usually makes up a large portion of retirement spend).

The Ugly

Did I say ugly? Sorry I mean to say fees and taxes!Even though these can have a huge impact, the above results (as well as the results the Prof Pfau got) ignore both fees and taxes.

- Although Tax can be minimised, you will do really well to get it to 0. You will likely incur Tax from annuity income, capital gains and dividends (and probably all three).

- Fees. Man this could be a biggie!

- If you were planning on using a 4% starting withdrawal, and your fees are 1% per annum, then it actually means a 3% starting withdrawal. That’s a full 25% less income every month - for the rest of your life! If you have an expensive financial adviser, who put you into an expensive annuity product, which invests in Unit Trusts, you could be bumping up against 2% and more likely 3% in fees. That leaves you with a best case of half your expected income!

- This is also one of the reasons I don’t like RA’s. You have to convert to an annuity product – although RA fees have been coming down, it is almost certain that it will be more expensive than a TFSA (for example), and the income from an annuity is treated as income for Tax purposes.

- Then there is also the cost of re-balancing - crossing spreads, brokerage etc.

I'm Still A Fan

So am I abandoning the 4% rule for my retirement planning? Absolutely not.I still think the rule is a great starting point, and it still gives a nice tangible number to shoot for. There are also a number of ways to handle both the problem of running out of money, and the problem of ending with too much money, but I think I will save that for another post (before this one turns into a novel!)

So, I am still very much all systems go on my 4% rule-based early retirement plan…

Till next time, Stay Stealthy!

- ~ - ~